Review – The Physicist and the Philosopher

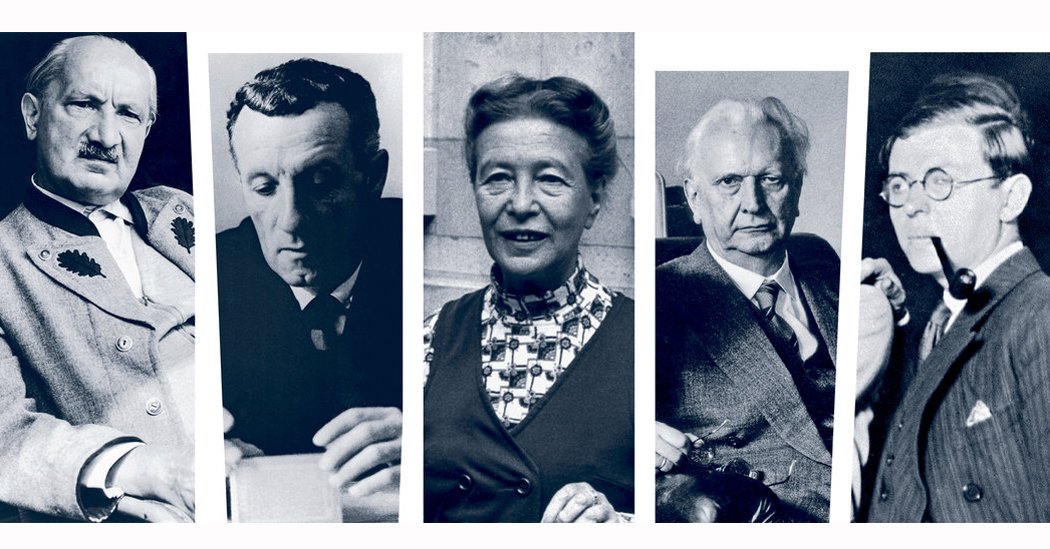

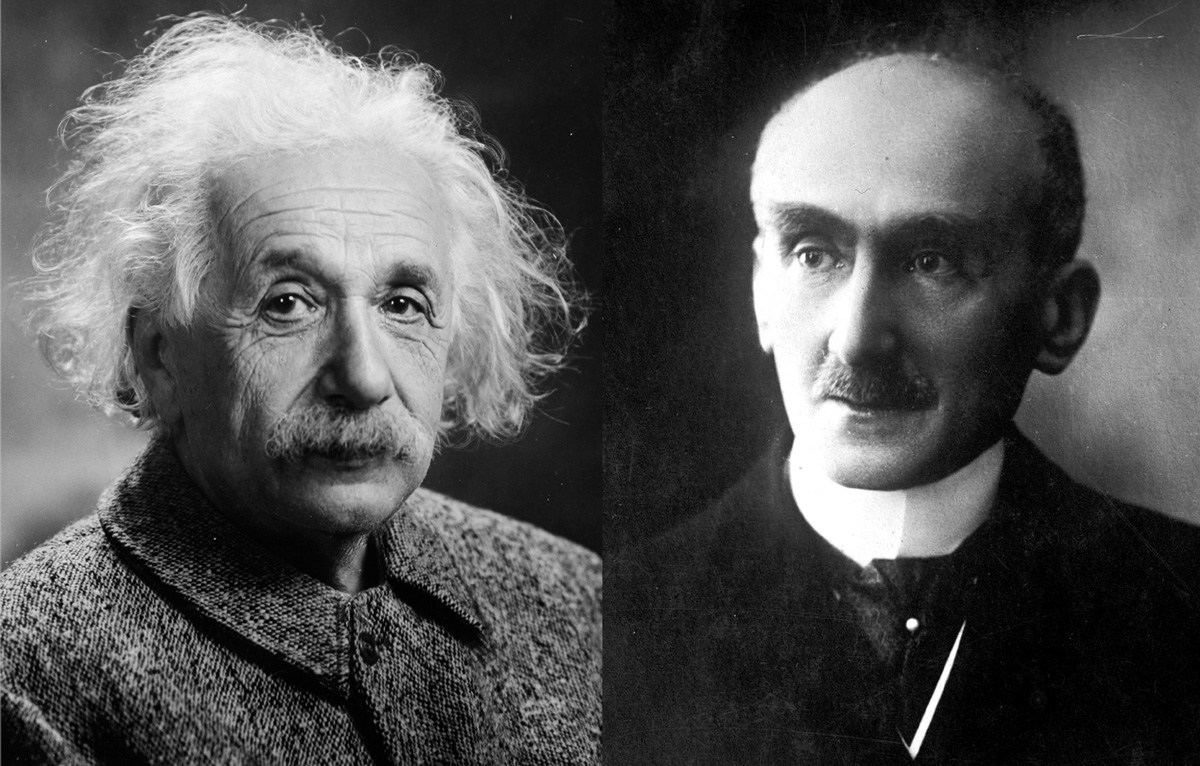

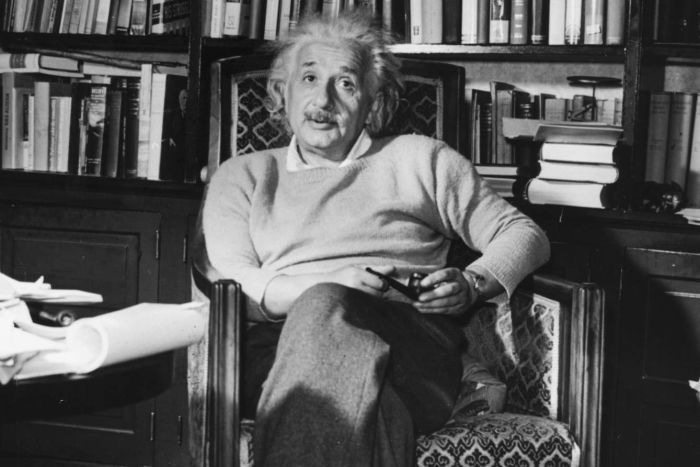

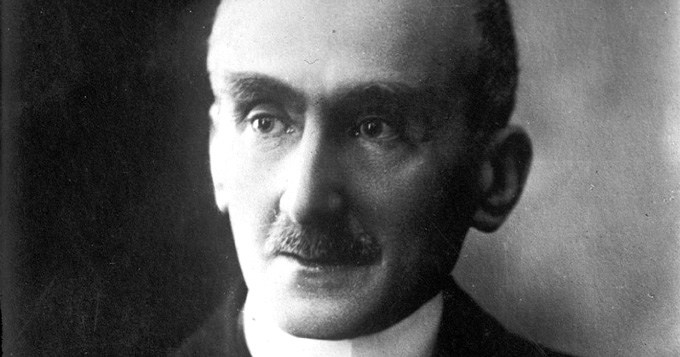

Jimena Canales tells the neglected story of Einstein and Bergson, the physicist and the philosopher. It is a story of a debate–a debate about time–that took place on April 6th, 1922. The mere mention of Einstein in a debate with anyone is enough to draw one in to hear more. But it helps, of course, that Canales recounts the arguments so well. We might think that Einstien was the famous one in this debate, but, historically, we would be mistaken. Einstien became well known after the famous eclipse expedition in 1919 that confirmed his theory, and, so, he was just beginning to see his stature rise at this time. But it was Bergson who was the established star.

Einstein’s bold claim during the debate (in front of philosophers no less) was apparently shocking to many present–and to Bergson in particular: The time of the philosophers did not exist.

Einstein saw the philosophical approach as describing psychological time–as such just describing ‘mistakes’ of our mind, mistakes that make us think time is speeding up or slowing down in our individual experiences (e.g., in our experience, say, of scoring a goal in a football match—our perception of the apparent time it takes the ball to roll past the goalie may seem to slow down significantly as we kick the ball off of our foot and into the goal). This psychological conception could be useful and valid when dealing with human understanding of everyday lives. But the new physical descriptions should ultimately replace this with a more accurate description of time that reflects objective reality.

Einstein claimed that Bergson “simply did not understand the physics of relativity–an accusation with which most of Einstein’s defenders agreed and which Bergson forcefully resisted. In light of these accusations, Bergson revised his argument in three separate appendices to Duration and Simultaneity…Bergson’s response has frequently been ignored” (9). Of course, as one might expect, Bergson claimed the opposite: they simply did not understand him.

Bergson also explained that “his qualms were not at all with any technical results or conclusions” (25).

So, what were his qualms? Well, this is what the book lays out for us in considerable and admirable detail. But, briefly, they were that time “was not something out there, separate from those who perceived it. It did not exist independently from us. It involved us at every level” and that he found

“Einstein’s definition of time in terms of clocks completely aberrant. The philosopher did not understand why one would opt to describe the timing of a significant event, such as the arrival of a train, in terms of how that event matched against a watch. He did not understand why Einstein tried to establish this particular procedure as a privileged way to determine simultaneity. Bergson searched for a more basic definition of simultaneity, one that would not stop at the watch but that would explain why clocks were used in the first place. If this, much more basic, conception of simultaneity did not exist, then ‘clocks would not serve any purpose.’ ‘Nobody would fabricate them, or at least nobody would buy them…Yes, clocks were bought ‘to know what time it is’…But ‘knowing what time it is’ presupposed that the correspondence between the clock and an ‘event that is happening’ was meaningful for the person involved so that it commanded their attention” (42-43).

Canales certainly covers quite a bit of ground in this book: she looks at many different aspects to this debate, from religious considerations (e.g., her chapter “The Church”) to quantum mechanics, leaving almost no stone unturned in those considerations. She also restores Bergon’s contributions. As she notes in her interview with Joe Gelonesi on The Philosopher’s Zone: “The disappearance of Bergson from, obviously science, and philosophy is astounding. So I was very shocked to go to the Stanford Encylopedia of Philosophy and look at the entry of “Time” and see, for example, that Bergson was not even mentioned. It’s an incredible reversal…” Canales does a service to Bergson’s point of view, especially since Einstein is seen as the victor on this issue, and that most who are at all familiar with the debate on time are familiar with Einstein’s view. But Canales does not short-shrift Einstein’s view (or those of his supporters) in this process.

On another note, I would have liked to see a brief but concentrated section on just the debate itself: a set-up of the players in the room maybe, and a description of the smells, sounds, and sights of the occasion; and, most important, a once-over and direct look at the arguments given. Maybe this would not have suited the book’s purposes or audience, but I think readers (especially those unfamiliar with the concepts and their histories) would have been well served by such an introduction–even if constructed as just a glimpse of the in-depth analysis given in the rest of the book.

However, the book is lively and engaging, and given the difficulty of the subject matter, Canales also does us a favor by being a clear, intelligent guide through the maze of arguments.