Rewind & Rewatch: The Prisoner – Arrival

I am starting a Rewind & Rewatch series on The Prisoner (the 1967 British series, created by Patrick McGoohan and George Markstein and starring McGoohan). I’ll be following the DVD episode order throughout this rewatch. In this series, I am merely looking for things of interest to me, ideas I find striking. This series is decidedly not a comprehensive review of The Prisoner, and these are certainly not my final thoughts on the TV series. It’s more like a set of notes. With any good piece of art, one can continually come back to it and find fecundity: missed elements, new relevancies, new avenues for thought.

And, of course, there is already quite a bit of media surrounding the series, e.g., Time for Cakes and Ale has a separate podcast (“The Tally Ho”) reviewing the episodes, there is a fantastic website dedicated to the show (The Unmutal Website, which has articles and links to more writing about the show)–and, of course, there are numerous pop culture references to it. Despite all of this great content, I still feel compelled (for the sheer love of the show) to demonstrate my deficiencies! So, here we go…

Episode One: Arrival

One must start with the title sequence and song–quite possibly the best TV has to offer! And, of course, its very structure ties into each show–the circuitous design of the opening title sequence is meant to throw us into dizzying thought, bringing us back into the mystery of The Village and its enigmatic pull on the main character. The intro is a mini-film in itself–and it gives the viewer the perfect introduction to the premise of the show.

The theme music, composed by Ron Grainer, is exciting and laden with the quintessential sounds of the sixties, with biting electric guitar, heavy percussion, and bright horns. The intensity of the music adds drama to the images and enhances the determination in our main character’s eyes.

We arrive with the character

The narrative throws us into the mix straight away with the opening theme sequence and subsequent first scene. We are the character, i.e., the character’s perspective is ours.

Our first look at The Village comes through subjective framing, right after a close up of McGoohan’s intense gaze. Again this sets up the series as a play on perspective and perception: What is real/unreal? Number Six is left to his own devices to unravel the mystery laid before him. He trusts his experience, and we, the audience, are encouraged to trust it as well. But is it trustworthy?

Seeing with the eye (I)

Number Six is a subject (an I-eye) presented with–what, in some sense, he perceives to be–an illusion, The Village. We, too, see this as an illusion. As noted above, the narrative structure of the series puts us clearly on the side of Number Six. As we have only experienced the world through his eyes, we take his experience as given, as correct. The series goes on to play with the audience on this, however. We are tempted throughout to doubt, at least from time to time, the veracity of Number Six’s perspective. But we are always brought back to his reality, his perspective.

Number Six has more information than we do, to be sure–he has lived a life in service of an organization that we are not privy to see. [And, as a side note, this has led some to believe that The Prisoner is, in some sense, a sequel or continuation of McGoohan’s series Danger Man (Secret Agent).] So, he knows things we do not (and the “information in [his head] is priceless”), but he is still our primary guide to this world.

However, one must also note that the audience is given ‘evidence’ outside of Number Six’s perspective, e.g., we see actors in The Village talking when Number Six is not there to observe–and this reinforces the reality of Number Six’s experience and realigns the audience with him.

What does this mean for us as an audience? What is real? Who/what can we trust?

The problem of illusion

In The Prisoner, Number Six is in a world of illusion, and, throughout the series, the villagers attempt to trick him into thinking his life has been a hallucination and that The Village reality is the correct one.

Again, there is a mix of reality/illusion that is difficult to decipher. Number Six is unraveling many mysteries that appear to lead to one giant puzzle. But is he? He has chunks of experience that seem real, but we are led to question even the ‘facts’ or ‘clues’ acquired in The Village. Is it leading anywhere at any given point? Or is this, too, part of the deception? The bigger question lingers: how do we get to the bottom of it all?

“Be seeing you”

The idea of being watched is ever-present in The Prisoner. But who is watching? Why are they watching? This episode certainly sets the stage for the mysteries of The Village, and McGoohan plays the combinations of perplexity, anger, and exasperation so well. His frenetic performance in this first episode gives us a sense of the danger of The Village–it is dangerous for several other reasons, but one of its most dangerous aspects is its soporific nature: it can lull one to sleep, to complacency and inaction. Number Six’s anger is a protection against these soporific elements, and it allows him to stay awake, to observe, and to take advantage where he can.

“My life is my own”

Number Two, the chief administrator of The Village, knows about McGoohan’s character so well that he can predict his breakfast choices (but he does not know everything, for example, his preference for lemon tea). There is a play on individualism, freedom, and determinism that starts here in this first episode and continues throughout the series. We, too, are seemingly born into this unknown situation (much like Number Six’s entrance into The Village, and we must make choices–and even no choice is a choice). The existential resonances are undeniable: we are thrown into this world–for example, as Satre noted, we are “condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, [we are] responsible for everything [we do].” (“Existentialism is a Humanism,” 1946); or one could look to Heidegger’s concept of “thrownness” (geworfenheit); or Camus’s notions of randomness, for example, as seen in his novels The Stranger or The Plague–not to mention the clear portrayal of the absurdity of The Village.

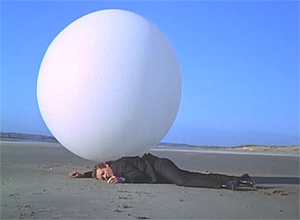

Rover

Just a last note on Rover: Rover as an image is compelling (even if it is often seen merely as a plot device to forego explaining the power of The Village to keep inhabitants there). The white balloon is non-descript (it could be almost anything), and yet this is one of its most potent aspects–that it can be anything, can contain multitudes; it suggests rather than defines. This may be frustrating to some who want mystery simply to be a problem that can be solved. But the series sees mystery as mystery–not merely as a problem to be solved but as a reality to be confronted and lived.

Thanks for reading–and I’ll be back soon to continue my rewatch of The Prisoner. “Be seeing you”…